Why culling has become a pressing issue in Marloth Park, South Africa:

-

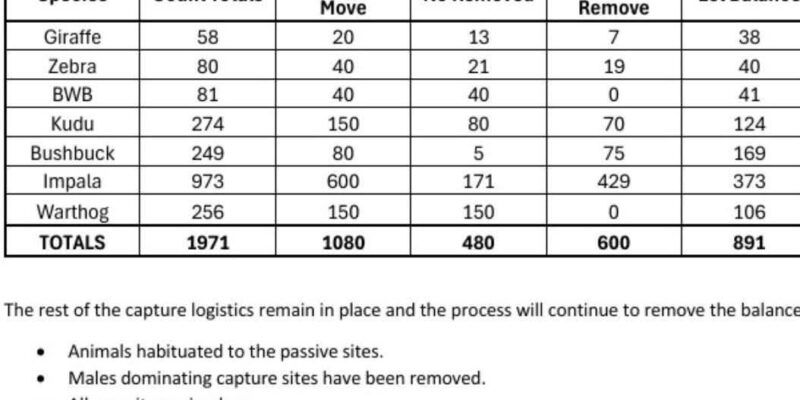

Severe overpopulation and habitat degradation

-

Wildlife in Marloth Park has increased dramatically, leading to extensive overgrazing, vegetation loss, and soil erosion. With no natural predators, herbivore populations like impala, zebra, kudu, and warthogs have grown unchecked, compromising both ecological balance and biodiversity worldwidewaftage.comcullingsa.co.za.

-

-

Starvation, disease, and suffering among animals

-

Reports by the NSPCA and veterinary experts have documented alarming animal suffering—starvation, malnutrition, injuries from competition over scarce resources, TB, and cachexia (extended malnourishment)

-

-

Legal directives mandating humane population control

-

In November 2024, the Mpumalanga High Court ordered the Nkomazi Local Municipality to immediately and humanely manage the population crisis. The court emphasized the provision of feed and veterinary care, pending more long-term solutions.

-

The order came after the NSPCA filed for relief, and a prior interdict from the ratepayers’ association had prevented any action since 2017.

-

Alternatives to culling—available but limited

-

Passive capture and relocation: This approach has been proposed and even implemented in the past (e.g., relocating animals to Lionspruit), but logistical and legal challenges, as well as associated costs, limit its viability.

-

Contraception/fertility control: Some residents and conservationists advocate immunocontraception or other non-lethal population control methods. These are slower and often costlier, making them less feasible in the face of immediate animal suffering and habitat collapse.

Why culling has been deemed necessary (not ideal, but urgent)

-

Immediate relief for suffering animals: With many starving, the speed of their decline makes long-term solutions—and the cost of implementing them—unfeasible without delay.

-

Ecological necessity: Left unchecked, populations far exceed what the land can support, risking ecosystem collapse and loss of biodiversity.

-

Legal compliance: The municipality is under court order to act quickly and humanely. Doing nothing would violate that order

-

Focus on humane implementation: Authorities and the NSPCA emphasize humane approaches—culling should be conducted ethically, with veterinary oversight, and ideally complemented by feeding and rehabilitation where needed.

Summary: When and why culling becomes necessary

| Situation | Risk / Consequence | Why Culling (or urgent action) is needed |

|---|---|---|

| Severe overpopulation | Habitat degradation, hunger, disease | Need to reduce population pressure quickly |

| Immediate animal suffering | Starvation, illness, injury | Urgent action to alleviate the crisis |

| Legal pressure | Court mandate to act | Requirement to fulfill legal obligations |

| Limited capacity for alternatives | High costs, time constraints | Culling is often the fastest and most viable solution |

The emotional and community context

Marloth Park is more than a wildlife reserve; residents and visitors have deep, emotional bonds with the animals. This makes the prospect of culling a painful and controversial one. Still, many parties, including the ratepayer association, have expressed willingness to support humane, properly managed solutions so long as safety and transparency are ensured

Culling in Marloth Park isn’t undertaken lightly. A combination of overpopulation, ecological collapse, animal suffering, and court mandates has created an urgent situation. While non-lethal strategies are preferable and supported in principle, the immediacy of the crisis and constraints on alternatives have rendered culling a necessary, if regrettable, part of the response.

Of course, this saddens us, as well as many others who love the wildlife in Marloth Park. However, with many births expected over the next few months, by the time we return next June, the reduced numbers may not be noticeable. Fortunately, none of the approximately ten members of Norman’s family will be culled.

Last night, we had a fabulous dinner at Jabula with Rita, Gerhard, and Inge. We’re looking forward to seeing them again tomorrow and on other days over the next week, until we leave in eight days.

Be well.

Photo from ten years ago today, September 6, 2015:

|

| A dingo, a wild dog, is found in the Australian Outback. For more photos, please click here. |